A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE SACRAMENTO NORTHERN

The Sacramento Northern Railway was once the largest interurban system in Northern California, and became the Western Pacific's most important subsidiary. Forged through the merger of two independent and very different electric railroads in 1929, the SNRY was a line with truly interesting equipment and many unique features.

The Sacramento Northern Railway was once the largest interurban system in Northern California, and became the Western Pacific's most important subsidiary. Forged through the merger of two independent and very different electric railroads in 1929, the SNRY was a line with truly interesting equipment and many unique features.

The kernel from which the SNRY's "Northern End" sprouted was a local streetcar line, the Chico Electric Railway. This five-mile trolley line opened for service on January 1, 1905. The line was built largely to serve Diamond Match Company's Barber mill just outside Chico, and most of its officers were Diamond Match men. The CERY enjoyed only a few brief months of independent operation before being sold to a new company, the Northern Electric Railway in November 1905. The new owners, closely linked with the Pacific Gas & Electric Company, went on to build an interurban system that blanketed the upper Sacramento Valley.

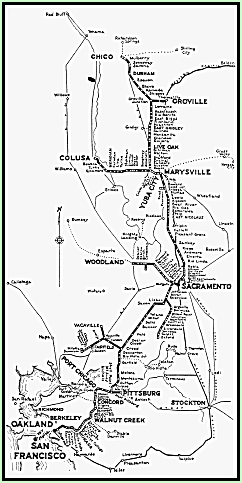

NERY's first interurban route, a 25-mile line between Oroville and Chico, opened in 1906. Soon the track was pushed south to Marysville. NERY's mainline reached Sacramento in 1907, making the interurban a serious competitor to the Southern Pacific in the upper Sacramento Valley. Over the next few years, the NERY added branches to Hamilton City, West Sacramento, Swanston (North Sacramento), and Colusa. The mainline was expanded from Sacramento to Woodland in 1912, later becoming more simply the Woodland Branch. A plan for extending the Woodland line to a ferry connection at Vallejo resulted in the isolated Vacaville-Suisun Branch in 1914. The NERY continued to offer streetcar service in Chico, and also operated routes in Sacramento, and between Yuba City and Marysville. By 1914, the NERY had reached its maximum size, 157 miles.

The NERY's mainline was powered by an uncovered 600 volt DC third rail, including the Mulberry shops and yard near Chico. Over city streets the cars took power with trolley poles from a typical overhead wire. PG&E supplied high voltage AC power, which was stepped down and converted by NERY-owned or PG&E substations.

The NERY was best known for its attractive poppy-orange Niles passenger cars with their five window ends, graceful clerestories, and art glass panels. Three powered combines and three powered coaches were initially purchased in 1906. These were followed by ten trailer coaches in 1908, two of which were later rebuilt as powered combines. NERY's ever-efficient Mulberry Shops built six more combines based on Niles' design in 1909. A luxurious parlor car named Bidwell, rebuilt from wrecked Niles coach 202 in 1914, added comfort and glamour to express trains. The line also owned three less stylish Cincinnati interurban cars, and four boxy, but sturdy, St. Louis cars. Combines headed nearly all NERY passenger trains. They could easily drag one, often two trailers over the line's easy grades. Four car trains usually had two power cars. Express trains provided quick service between Chico and Sacramento with names like the Bay Cities Limited and The Steamer Special. Locals were usually limited to just two cars, and most branches were served by single cars.

Early streetcar service was operated with six wood-bodied double-truck St. Louis streetcars, similar to the "Huntington Standard" cars with both open and closed sections so popular in Southern California. Two St. Louis open bench cars were also used in warm weather. All the double-trucked streetcars were later rebuilt with completely enclosed bodies. Four small wooden single-truck cars were purchased from United Railroads of San Francisco, but operated only a few years before being sold or scrapped.

Freight trains moved behind a small fleet of locomotives, most built in the Mulberry Shops. There were two all-steel steeple cabs for local switching, two powerful all-steel box cab motors for mainline service, and five general-service composite flat motors. An additional flat motor, originally built by Diamond Match for the CERY, was used on some light-traffic branches. To provide service to shippers, the NERY owned a modest fleet of freight cars. The fleet included 50 36-foot wooden truss-rod boxcars and at least 170 40-foot wooden flatcars delivered by the Fitzhugh-Luther Company in 1907. American Car & Foundry provided 50 identical boxcars in 1908. Additional rolling stock, such as six stock cars added in 1917, was built in the Mulberry Shops.

As was so often the case with new railroad ventures of the time, the NERY was bankrupt by 1914. New investors incorporated the Sacramento Northern Railroad Company and bought the NERY on June 28, 1918. The new company made no major changes to the interurban fleet, with the exception of buying another parlor car, Henry Huntington's famous private car Alabama. All-steel Birney Safety Cars replaced most of the wooden streetcars. Several older streetcars were rebuilt in the 1920s as Elverta Scoots which offered suburban service to the growing towns immediately north of Sacramento. Rather than building more locomotives in the Mulberry shops, off-the-shelf Baldwin and GE steeple cabs were purchased instead.

SNRR control passed to the WP in 1922. Under WP ownership, the line added several more freight motors from GE and Baldwin, most dual voltage 600-1200 volt units. In 1925 a fine interurban terminal was built in Sacramento to serve the SNRR, San Francisco-Sacramento Railroad, and the Central California Traction Company. On November 4, 1925, the SNRR was sold to the Sacramento Northern Railway Company, a WP subsidiary specifically designed to consolidate and manage their growing interurban railway holdings.

The "South End", lines south of Sacramento, were built by the former Oakland & Antioch Railway and its successor the Oakland, Antioch & Eastern Railway, between 1911 and 1913. Beginning at the Key System's Oakland Ferry terminal, the line traversed Key System private right-of-way and city streets to reach home rails at 40th and Shafter where a modest yard and shops were located. After heading northeast on Shafter Avenue the track moved onto private right-of-way, encountering a fearsome ruling grade exceeding 4.5%. This was followed by a lesser grade of 2.2%, as the route climbed through the Oakland Hills. At the summit was the 3,600-foot Redwood Peak Tunnel, the only tunnel on the system. Beyond the tunnel, the route touched several important East Bay suburban communities: Lafayette, Walnut Creek, and Concord. Again heading northeast, the track made a bee line for Sacramento through the largely empty delta country. Branches reached out to Walwood, Danville and Pittsburg, making the system's total length 115 miles.

To carry the line across Suisun Bay, a massive high-level bridge with a central draw span was planned near Pittsburg. As a temporary measure, a gasoline-powered, wooden car ferry named Bridgit was launched in 1913. The ferry operated less than a year before being destroyed by fire. A replacement, the all-steel Ramon, was rushed to completion in 1915. Due to tight money, the bridge was never built, and Ramon became a both permanent feature and an operating bottleneck for the next 38 years.

Electric power was supplied at 1200 volts DC, with 600 volts DC used over Key System track and in the line's own Oakland yard. Distribution was by suspended wire in the typical interurban fashion. Pantographs were used for power pick-up on the Key System, but trolley poles collected power under OA&E's own wire. High voltage AC power was purchased from Great Western Power Company, and converted in the OA&E's own substations.

The OA&E purchased 16 business-like composite combines from Holman, Wason and Cincinnati, all essentially to the same design. They weren't particularly attractive cars, and their Pullman green paint was rather somber, but they were powerful and gave adequate service for 28 years. They were delivered as bodies, and powered with motors and trucks purchased from the bankrupt Ocean Shore Railway. Two smaller Holman-built combines inherited from the O&E were used mostly on the Pittsburg and Walwood branches. A hideous, leaky combine was rebuilt from an ancient SP car to cover Danville service. The combines were supplemented by eight all-steel trailer coaches from Hall Scott Motor Car Company of Berkeley, three of which were later motorized. A gaggle of used, and very uncomfortable, trailer coaches from the SP and the OSRY carried commuters at peak hours and were also used for weekend picnic trains. Two classy parlor cars, Moraga and Sacramento, brought up the rear on top express trains.

Minimal freight service was provided by four Baldwin steeple cabs. Two of these were 62-ton monsters with pony wheels, originally designed as high-speed passenger locomotives to pull the steel coaches. They proved too heavy for the Key System pier and were banished to freight service. The other two locomotives were light switchers. Two composite express motors were used for lighter freight duties. The OA&E owned just a handful of wooden truss-rod boxcars and flatcars built in 1911 and 1912, plus a few much older cars purchased from the SP.

The OA&E was soon in poor financial condition, with revenues far below expectations. This was especially true in the freight column, as the line initially served no major industries. In 1920 the railroad was reorganized as the San Francisco-Sacramento Railroad. The money-losing Danville and Walwood branches were lopped off, but the new company was still unprofitable. The only major change to the rolling stock was scrapping the Danville combine and using its trucks and motors under a third box motor. On August 1, 1927, the SF-S was mercifully sold to the WP, and was it merged into the Sacramento Northern Railway on January 1, 1929.

WP control and the merger brought many changes to both interurbans. The freight locomotives from both lines were renumbered to avoid conflict with the passenger cars. Strictly 600-volt locomotives became the 400 series, while 1200-volt and dual-voltage locomotives from both lines were grouped in the 600 series. Former OA&E dual-voltage passenger motors, which could operate over the whole system, now led trains through trains all the way from Oakland to Chico. The stately Niles cars could not operate south of Sacramento and were largely assigned to "North End" branch and local service. The new freight-only Holland Branch opened in 1929, with a pressure of 1500 volts DC. The higher voltage meant less power loss and greater horsepower for the locomotives. The pressure on all lines south of Sacramento, except the Woodland and Vacaville-Suisun branches, was raised to 1500 volts in 1936, and the 1200-volt cars and locomotives were converted to the higher voltage. The isolated Vacaville-Suisun branch was joined to the mainline at Creede in 1930. Also in 1930 the Pittsburg Branch was extended to the United States Steel's Columbia works, which in time become the SN's most important freight customer. The biggest improvement was completion of the San Francisco Bay Bridge, with its high speed rail lines on the lower deck. SN service into downtown San Francisco over the bridge began on January 15, 1939.

Sadly, the Great Depression and automobile competition had already cut deeply into passenger revenues. Dining car service was dropped in 1936, and parlor cars were removed from regular trains in 1938, though they were frequently chartered by railfans in the final years. Strict economies could not stop the red ink. Passenger service between West Pittsburg and Sacramento ended August 26, 1940. On October 31, 1940, the last passenger train ran between Chico and Sacramento. The final regular passenger trains on the "South End" ran June 30, 1941. As passenger service wound down, the once-proud interurban cars were burned for their scrap metal at Chico.

Marysville-Yuba City streetcar service was replaced with busses on February 16, 1942. Streetcar lines in Sacramento were sold to Sacramento City Lines (a National City Lines subsidiary) in 1943. The trolleys were replaced by busses in 1946. Chico streetcar service held on until December 15, 1947, making it the SN's last regular passenger operation. Perhaps it was fitting that SN passenger service should end in Chico, the city where it all began.

After their early success with SW-1 and FT diesels, the WP management was committed to dieselization on all its lines, including the SN. Full dieselization on the SN was out of the question while World War II was raging. Only the section immediately north of Sacramento with its deadly third rail through suburban neighborhoods had been de-electrified by 1944. Freight trains were pulled by WP switchers from Sacramento on the night shift, usually by WP 511, an ALCO S-1. When six 44-ton GE diesels arrived in late 1946, the SN could finally turn off power to nearly all its third rail lines.

On July 24, 1951, a heavy Pittsburg-bound steel train collapsed the Lisbon trestle south of Sacramento, punching the first hole in the SN's mainline. The trestle finally reopened in 1954 without overhead wire. With the trestle's reopening, the ferry Ramon ceased operation on April 7, 1954. Mainline track between Sacramento and Chipps was now reduced to a dieselized branch operated from Sacramento. The important Pittsburg steel traffic was rerouted via the WP to Stockton, and from there to Pittsburg over the Santa Fe by trackage rights. WP diesels were borrowed for the steel trains. In 1957, the SN purchased a pair of used F-3 diesels from the defunct New York, Ontario & Western Railway to cover this service.

The Oakland section had performed heroically during World War II and the Korean War, moving thousands of cars filled with vital military supplies to the Oakland Army Base via the Oakland Terminal Railway (jointly owned by the WP and Santa Fe after 1942). With its stiff grades, street running, and a freeway crossing at grade, the WP saw the SN's Oakland line as a costly liability. It was not until 1957 that a direct connection between the WP and the OTRY was finally built along Union Street in Oakland. This made the old OA&E mainline completely redundant, and most remaining electric locomotives surplus along with it. After the last SN train left Oakland February 28, 1957, the track was cut back to Lafayette and the remainder dieselized.

GE steeple cabs 653 and 654 were the last electric locomotives in operation on the SN after 1957, working the short section between Marysville and Yuba City. A stiff eastbound grade at Yuba City, exemption from full crew laws, favorable power rates, and a lack of money for more diesels, kept the electric locomotives running for a few more golden years. These conditions couldn't last forever, and in 1965 new road diesels on the WP made two SW-1s at the bottom of the food chain available for SN's Yuba City operation. After 654 headed a final excursion train on April 10, 1965, power was turned off for the last time.

Over the years the SN's mainline was chopped into short branches, often reached by trackage rights over the WP or the SP. Most SN traffic was in highly seasonal agricultural products. This business was especially vulnerable to truck competition, plant obsolescence and changing markets. By the time the SN was folded into the Union Pacific in 1983, the line was but a shadow of its former self. Today nearly all SN track is gone, or lies dormant. The only major pieces in regular service are the former Woodland Branch, now operated by the Yolo Short Line, and some industrial track in West Sacramento. A restored mainline section near Rio Vista Junction is operated under wire by the Western Railway Museum.