HAVENS, SN'S VITAL MIDDLE OF NOWHERE

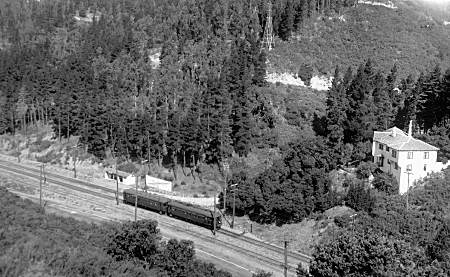

Havens station, which served but a handful of passengers, was nonetheless one of the Sacramento Northern Railway's most important operating features on the South End.

Havens was located in the steep and narrow Shepherd Canyon in the Oakland Hills at the junction of Paso Robles Drive and Park Boulevard (now known as Shepherd Canyon Road, though the alignment is somewhat different). According to the late author and historian Harre Demoro, Havens was one of the numerous subdivisions planted throughout Oakland and the nearby hills by the Realty Syndicate at the beginning of the twentieth century. The Realty Syndicate was the brainchild of Francis "Borax" Smith and Frank C. Havens, promoters of the Key System Railway, the Claremont Hotel, and many other East Bay developments. There is some disagreement whether Havens was named for Frank C. Havens, or one of his relatives, but the subdivision did immortalize the family name.

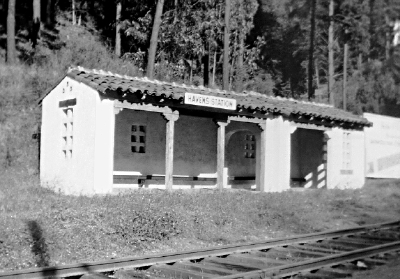

When the Oakland, Antioch & Eastern Railway began regular operation through Shepherd Canyon in 1913, the Realty Syndicate had high hopes that Havens would take off as an upscale subdivision. The most prominent feature at Havens was a large mission-style stucco passenger shelter. The building was unlike any other depots on the OA&E, but was similar to shelters on the Key System, for example the Underhills station at the end of their B-line. According to Demoro, the structure was actually built by the Realty Syndicate to promote the subdivision.

Unfortunately, Havens flopped badly. Perhaps the subdivision failed because nearly all the flat land in the canyon was occupied by the railroad and few buyers wanted to build on the steep canyon sides. One very prominent house did cling to the canyon wall (it's still there), with a few more homes strung along the ridge far above the station. In any case, the Realty Syndicate went bankrupt around 1915 along with much of the Smith-Havens empire.

In passenger days very few passengers boarded or got off the interurbans cars at Havens. With a paucity of nearby homes, the trim shelter saw very few commuters. One may hope that any long-distance passengers who used the shelter came or went from there by automobile. The climb to the canyon rim would have demanded a lot of huffing and puffing, especially with a suitcase or two.

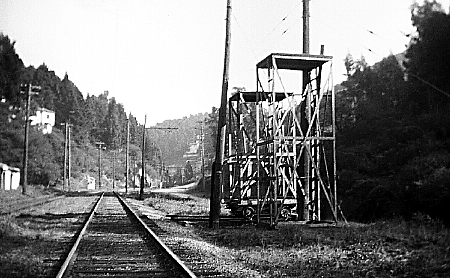

Railroad-wise, Havens was 5 1/2 miles east the 40th and Shafter yard, and about 1/4 mile west of the 3,700-foot Redwood Peak Tunnel's mouth. According to SN's Employee Timetable 23 (of 1953) the siding was about 400 feet long, and could hold nine 40-foot freight cars. A single-ended spur coming off the mainline just east of the siding switch could hold ten cars. Earlier timetables rated both spur and siding for an additional car each. There was a small railroad-owned telephone booth by the siding's east switch. Handcar set-outs were placed along the mainline roughly opposite the station. The grade through Havens was over 2 percent, rising eastbound to the summit at the tunnel.

With the descending westbound grade exceeding 4.5 percent near Lake Temescal, every precaution had to be taken to prevent runaway trains. In passenger days, all westbound freight trains were required to stop at Pinehurst for brake tests and inspection. An inspector was regularly dropped off by passenger trains at Pinehurst to handle this job. When passenger service ended, brake inspections were moved to the now-dormant Moraga depot, where road access for the inspector was much better than at Pinehurst. Tools and spare parts were kept at the Moraga depot for emergency brake repairs. After the inspection, the conductor, engineer and car inspector were all required to sign the brake test card, form 182.

Westbound trains stopped again at Havens where the brakeman turned up the retainers on all cars. Brake piston travel was adjusted to no more than seven inches. Ninety pounds of brake pipe pressure, with a main reservoir setting of 110-130 pounds, was required on westbound freight trains. The brake inspection card was deposited in a box at Havens.

The danger of runaways was taken very seriously. On March 30, 1913, Oakland newspapers reported that a gondola had gotten loose and hurled down the grade, reaching a speed estimated at 70 miles per hour. As the car raced across the Shafter and College intersection, it struck a Key System streetcar and injured eight passengers. Then the gondola left the rails on the curve, took out a eucalyptus tree and a telephone pole, demolished an unoccupied real estate office, and finally struck a nearby home with the car's load of lumber ending up in the basement.

In later years, some juvenile delinquents stole one of the SN's tall maintenance push cars at Havens and sent it flying downgrade. According to Bob Campbell, Oakland police spotted the runaway car and were able to block cross streets on Shafter Avenue. The car rolled harmlessly into the Shafter yard, where amazed SN crewmen discovered it the next morning. After that adventure, the cars at Havens were chained down, and the foreman was required to remove a wheel from each car. The loose wheels were kept in the foreman's pick-up until needed.

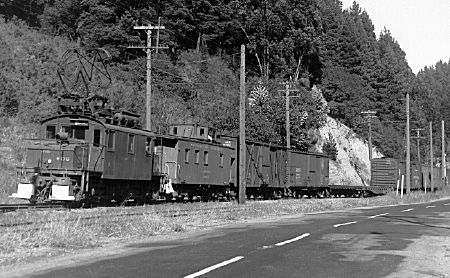

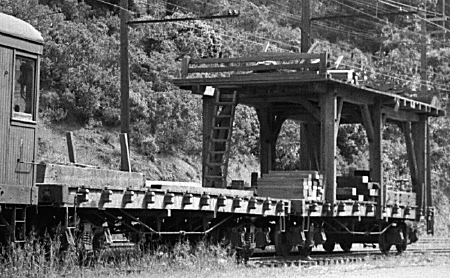

Havens' spur was used as the base camp for repair crews working on the nearby tunnel. Work trains would be stashed on the spur, often consisting of a kitchen car, various living cars, and cars with tools and materials. A box motor was usually assigned to the work train. When working on the tunnel roof or the wire, the box motor would shove one or more "jumbo" cars (flatcars with a high platform at one end) into the tunnel. When scheduled trains were due, the work train had to scramble back down from the tunnel and into the siding at Havens.

The spur occasionally served as a team track, especially for the McGuire and Hester Construction Company. Other local shippers unloaded at the spur to save additional freight charges to Oakland or other locations to the west. Unloading at Havens ended during the 1950s, as it is not listed as a team track location in Western Pacific's Circular 167-E. The spur was no doubt also used to switch out occasional bad order cars.

The last regular SN freight train through Havens ran on February 28, 1957. The WP's new Union Street connection with the Oakland Terminal Railway made the electric line redundant. Soon the rails and wire were removed between Oakland and Lafayette. Within a few years, the Shepherd Canyon's walls were covered with up-scale homes. Curiously, the flat area along the now-empty right-of-way at what is now Bishop Court was the last section to be developed. It was not until 2007 that the last lots were filled in. Although it took almost 100 years, Havens has finally became a success as a residential neighborhood.