SACRAMENTO'S UNION TRACTION DEPOT

Transit chaos reigned in Sacramento during the 1920s, with three different interurban railroads operating from three separate terminals.

The Sacramento Northern Railroad inherited the Northern Electric Railway's old depot at Eighth and J Streets, by then spruced up with a mission-style facade. The San Francisco-Sacramento Railroad, successor the Oakland, Antioch & Eastern, used a small depot at Third and I Streets near the Southern Pacific station. After bouncing around various locations, the Central California Traction Company was operating from a cigar store at 1024 Eighth Street, apparently shared with a Western Pacific ticket office. The SNRR and the CCT cars loaded in busy city streets, and with growing auto traffic, this presented a serious safety issue. Passengers had to use streetcars or taxis to make connections between the three interurbans, with the Western Pacific and Southern Pacific steam trains, or with river steamers. This could be quite an adventure while toting several trunks or other luggage.

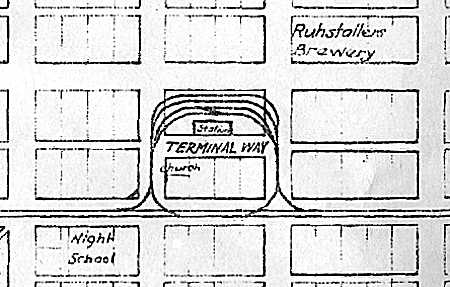

Terminal Way. Wyes on I Street allowed cars to enter and depart the station in any direction.

Garth G. Groff collection.

There had been considerable agitation for several years by Sacramento's city fathers, business groups, and an annoyed public, for a "union" traction terminal. Now facing growing automobile competition, the three electric lines saw the wisdom a shared depot, but the money just wasn't available. Enter the Western Pacific, which gained control of the SNRR in late 1921. The WP had its eye on all three electric railroads as potential feeders, and soon bought in to the idea of a joint depot. The SF-S, weakest of the three electric lines, didn't have enough money for their share of the terminal project, so the WP advanced them the cash, giving the steam road partial control of the interurban.

The depot was sited on a block bounded by H Street between 11th and 12th Streets. The actual front of the depot building faced an alley between H and I Streets. The alley was somewhat widened and renamed Terminal Way. The SNRR's passenger mainline already ran down I Street, but reaching the depot's four track yard on the block's H Street side required turns from I Street onto both 11th and 12th Streets. Wyes were provided at the intersections to allow trains to enter and leave the terminal by both directions on the proper side of the street. All trains operated through the terminal counter-clockwise. Local trains to Woodland, and those headed immediately back to their respective origins, used the terminal as a quick reversing loop. Initially there were no regular through trains, except for parlor cars. Through trains would come later in 1929 when the SF-S was merged into the SNRY.

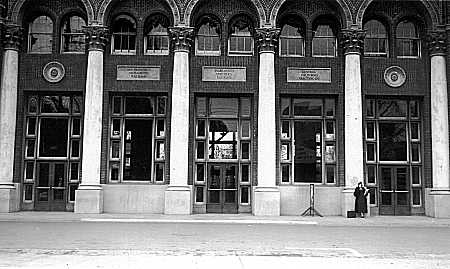

The Terminal Way side of the depot, seen here in 1938, shows the impressive five-arch facade,

typical of civic architecture in the 1920s. Even at this late date, the station hosted 22 daily trains.

Garth G. Groff collection, via the Wilbur C. Whittaker collection.

The station's designers seem to have had some sort of edifice complex. As originally planned, the building covered the entire block between 11th and 12th Streets facing Terminal Way. The imposing two-story central waiting room was to be flanked by single-story wings for baggage/express rooms and commercial shops, six bays on the west end and five on the east. Reality set in pretty early, and the wings were lopped off to one bay on each end. The west bay housed the express office, and the one on the east was leased out as a small restaurant. The latter bay was added after the depot opened.

The depot was a first class example of 1920s' civic architecture, and though smaller, had a similar appearance to the Southern Pacific's Sacramento depot. The traction terminal was built of brick and concrete on a steel frame. The imposing front was done in a Corinthian style, with five large arches. Floors were dark red cement on the main level, and pine on the upper levels. Walls in the 50 x 80 foot central waiting room were rough-tooled plaster, with Oregon pine trim. The ticket counter, concession stand, telephone booths and seats were made of oak. The mezzanine above the waiting room housed offices used by the SF-S, while the SNRR occupied the second floor proper, including space for their dispatcher. The building was said to have cost $350,000.

The station's rear side was rarely photographed by railfans, who usually pointed their

cameras only at the interurbans. A complete view was made by Sacramento's McCurry

Studio upon the opening of service. The SNRR combine is pulling two trailer coaches.

McCurry photo; courtesy of the Western Railway Museum Archives.

When the new terminal opened for business on September 20, 1925, only the SNRR and SF-S shared the new station. The CCT did not begin operating from this location until March 17, 1926, offering six round trips a day (according to a 1927 timetable). Moving to the new station did little to stem the CCT's growing losses from their interurban passenger business. The CCT's ridership declined as the highway to Lodi and Stockton improved and attracted more autos, plus direct bus service. Permission to abandon interurban passenger service was granted by the California Railroad Commission on February 3, 1933, and that very day the last CCT interurban car departed Sacramento.

Chico will take three hours. Equipment for trains 3, 8 and 48 share the H Street yard.

Kenneth C. Jenkins photo; Garth G. Groff collection.

The SF-S was acquired by the Sacramento Northern Railway on August 1, 1927. The actual merger of the two lines did not take place until January 1, 1929. Thus began the SNRY's golden era of through service from Oakland (later from San Francisco) to Chico via Sacramento. Three round trips a day were offered through Sacramento. In addition, there were eight round trips on the Woodland branch. Suburban "Scoot" service was offered along the mainline through Del Paso, and Rio Linda to Elverta. Branch line service ran through North Sacramento to Swanston. Both suburban routes initially operated eight round trips a day. Elverta and Swanston runs ended in 1933.

Southbound through trains had their third rail shoes removed during their brief stop in Sacramento. The shoes were reapplied to the cars on northbound trains.

By the late 1930s, the WP management had decided that their remaining interurban passenger service could not be made profitable. August 26, 1940, saw the last through passenger trains from Oakland to Sacramento. On October 31, 1940, the last trains were run between Chico and Sacramento, and also on the Woodland Branch, ending all service at the union terminal.

Depot." The SN dispatcher continued to occupy offices on the second floor until the 1970s.

Kenneth C. Jenkins photo; Garth G. Groff collection.

In the spring of 1941 the yard tracks along H Street and the wyes in I Street were removed. Part of the depot building was leased out as grocery store know as "The Food Depot". When the neighborhood decayed and the grocery failed, the main part of the building stood empty. The SNRY dispatcher continued to have offices on the second floor until they were consolidated with the WP dispatchers office around 1970. Shortly after the move, derelicts broke into the building and set the place on fire, causing considerable damage. In January 1972 the old depot was torn down, and a Best Western motel was built on the site.

the yard area now a parking lot. The little restaurant in the upper left corner is still in business. Cartwright Aerial Surveys photo; courtesy of Bill Calmes.

Material from this story was gathered from Ira Swett's SACRAMENTO NORTHERN; Harre Demoro's "Sacramento Northern Railway" in the NRHS BULLETIN, Volume 37, No. 6; and William Burg's SACRAMENTO STREETCARS. Full citations for these works can be found in our bibliography. Additional information was gleaned from "Union Station Built at Sacramento" found in the June 5, 1926, issue of ELECTRIC RAILWAY JOURNAL, and from CENTRAL CALIFORNIA TRACTION COMPANY by David G. Stanley and Jeffrey J. Moreau (Berkeley: Signature Press, 2002). Special thanks to Bill Calmes, Cartwright Aerial Surveys president, for the aerial photo.