SACRAMENTO NORTHERN PARLOR CARS

Top interurban railways of the early 20th century proudly offered their riders luxurious parlor cars comparable to the best available on their mainline competitors. The Sacramento Northern and its predecessors fielded FIVE fine parlor cars, each one unique.

The Oakland, Antioch & Eastern owned two parlor cars almost from the start of operations. The first was Moraga, built by Wason in 1913 as an observation and dining car. Moraga was originally a powered car, with four Westinghouse 322E motors, dual Westinghouse 15A2 controls, and was equipped with a pantograph and two poles. The motors, pantograph and poles were removed in 1915 and later applied to Hall Scott coach 1026, though Moraga retained her controls for backing movements on the Key pier. In her original configuration, Moraga had open observation platforms at both ends, since there was no way to turn the car in Sacramento. Shortly after the Sacramento Union Station was opened in 1925, Moraga was rebuilt as a single ended car. Moraga's original assignment was northbound on the Capital Limited and southbound on the Metropolitan. Later these two trains were renamed the Comet (both north and southbound). Moraga had a kitchen and dining area from the start, and light meals were offered to both parlor car patrons and regular passengers.

It was clear to the OA&E right from the start that a second parlor car would be needed. Cincinnati-built combine 1016 was rebuilt in the Oakland shops immediately upon delivery. Her baggage doors were removed and replaced with windows and siding. The walk-over seats were replaced with wicker chairs. The rear vestibule was enlarged, and opened out into a classic open observation platform. No kitchen or dining section was added at this time. The car was named Sacramento and entered service on the Meteor. In 1920, Sacramento finally received a kitchen and dining section, along with a bizarre growth spurt to a gargantuan 76-foot length (up from the original 55 feet). After protests from the Sacramento Northern Railroad that the car would not get around curves at Sacramento, Marysville and Chico, the San Francisco-Sacramento Railroad chopped ten feet out of the center and patched the car back together, giving Sacramento its final form. In later years, Sacramento became the regular parlor car on the Sacramento Valley Limited.

The Northern Electric Railway was slower than the OA&E to add parlor cars to their roster. It was not until 1914 that the famous Bidwell was built in the Chico shops. Bidwell was built as a trailer using the frame and trucks of wrecked powered coach 202 in the style of the line's other Niles cars. Bidwell was christened at an elaborate public ceremony on January 15, 1915, and entered service on the Bay Cities Limited, a top train between Chico and Sacramento. The car also served on the Sacramento Valley Limited. A kitchen was added in 1921, but by then Bidwell was mostly used as a relief car, and by company officers for inspections or business trips. After the tragic loss of sister car Alabama in 1931, Bidwell returned to regular service on various named trains. Bidwell received a set of massive Standard C-80-P trucks in 1937 which, to some observers, spoiled her classic lines. According to photographic evidence, Bidwell was the only SN parlor car fitted with diaphragm curtains (but not diaphragms!). They were fitted to the forward end of the car to aid passengers in crossing from the coaches. These curtains were apparently short-lived.

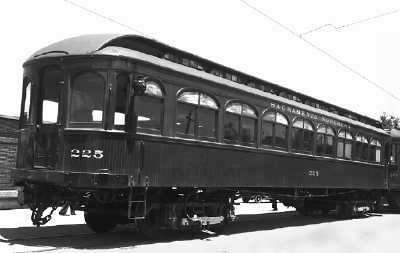

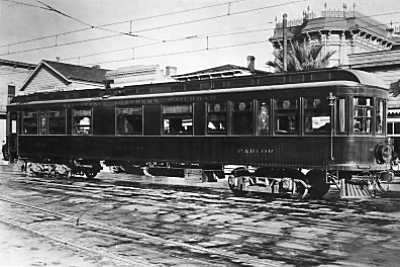

The parlor car that wasn't is one of the enduring mysteries of the SN's complex history. This was Niles trailer coach 225, one of the Northern Electric Railway's original 1906 cars. This car was wrecked in a collision at Front and "M" Streets in Sacramento on February 24th, 1919. It was rebuilt as a semi-parlor car with an enclosed observation platform (though retaining the train door). The steps and side doors were completely removed from the rebuilt end, and the toilet compartment was moved to the center of the car. There is no mention of any special seating or other luxuries on this car. Apparently seats in the observation end were the same dual walk-over seats as used in the rest of the car. The reason for the conversion is not clear today, but possibly the rebuilt 225 was meant to be a relief car for Bidwell, the SNRR's only parlor car at that time. There is no mention of 225 in parlor car service in any references, though it did bring up the rear of local trains as a regular coach on the North End.

The Sacramento Northern Railroad felt they needed another real parlor car, and in 1920 found a bargain with the purchase of Alabama. This was the marvelous private car of traction magnate Henry E. Huntington, builder of the Pacific Electric Railway. Alabama was built in 1905 by the Saint Louis Car Company, and was arguably the finest, most opulent interurban car ever constructed. The massive 63-foot car was built with a steel body (made to look like wood siding), and was fully up to steam railway standards. When Huntington sold the Pacific Electric Railway to the Southern Pacific, Alabama was not included, and was kept in shed on his estate in San Marino. The PE's new owners were cool to allowing Huntington's toy to roam their tracks at will, so the car saw little use after 1910. The SNRR bought only the car body and unpowered Hedley trucks. Alabama's motors and poles were used to build PE steeple cab 1599 (ironically built to the same plans as NERY freight motors 1000 and 1001).

The Mulberry Shops modified Alabama in 1920 and again in 1921 for service as a parlor car, making various interior changes, enlarging the dining section, adding a train door in one end, and substituting a Baldwin MCB truck for one of the car's original Hedley trucks. Full dining car service was offered aboard Alabama, in contrast to the smaller cars which served only light meals. In October 1921, Alabama went into service on the Sacramento Valley Limited and later on the Meteor. It was on the latter train that Alabama met her end on March 22, 1931. A fire which started in the electric coffee percolator quickly spread to the car's wooden interior. The helpless crew shoved the blazing car into a siding at Dozier, and within minutes the once-great interurban car was a smoking shell.

A small part of Alabama lived on briefly; her Hedley trucks were remotorized and appeared about 1935 under freight motor 404 in one the Mulberry Shops' frequent truck swaps. The experiment was short-lived, and 404's Baldwin MCB trucks were soon restored to their proper place. The Hedley trucks disappeared into history.

A few other souvenirs of Alabama still exist. Three leaded glass panels that were removed during the car's rebuilding are now in the collection of the Western Railway Museum. A bookcase currently owned by a descendent of the SNRR's master carbuilder is also preserved. It has been promised to the WRM.

George T. Dunlap had contracts to operate the dining car service on both SF-S and SNRR trains from 1923 to 1928, as well as the lunch room aboard Ramon. Dunlap was a caterer, and was one of the most prominent black business men in Northern California. There were many complaints about the quality of the food aboard SN trains, so Dunlap's contract was terminated in June 1928. The Western Pacific's dining car department took over SN dining car service. All food service ended in 1934, a victim of Depression-era losses.

Despite the loss of the dining car service, the parlor cars continued regular service on the Comet and the Meteor until 1938. Passenger service was piling up huge amounts of red ink, and the parlor cars no longer paid for themselves. However, SN President Harry Mitchell, always friendly to railfans, made the cars available for excursions and for charters on regular trains. On these excursions the parlor cars still carried the drumheads for the SN's famous named trains, and were widely photographed by railfans. In the last few months of operation, President Mitchell put the parlor cars back into service on a few trains as a nostalgic last gesture to passenger service.

With the end of passenger service in 1941, most of Sacramento Northern's fine interurban cars were taken to Chico and were burned for their scrap metal. Sacramento and Moraga, along with 225, met their inglorious end in the fall of 1941. Bidwell had a kinder fate. The body of this beautiful car was sold to a private individual who used it for many years as a dwelling in Wheatland, California.

In the mid-1970s, members of the Bay Area Electric Railroad Association acquired title to Bidwell (reportely in exchange for a new mobile home). The car was trucked to Rio Vista Junction where it was placed in closed storage inside a shed. And there the has car sat for over 30 years, rarely seen by visitors, but at least protected from the elements. Plans are underway to eventually restore Bidwell to her former glory. With a lot of work, and a lot more money, someday we may be able to ride in Bidwell behind 1005 and 1020 over a section of original SN right-of-way.

There is one other parlor car associated with the SN that deserves mention here. Salt Lake and Utah 751, a steel car with an open platform, was one of the early cars acquired by the BAERA. SL&U 751 was used on many excursions over the SN's remaining electrified South End trackage between 1950 and 1957. Usually it was pulled by 1005 or MW302. The parlor car was also used on the last diesel-powered train across Sacramento's Tower Bridge on November 15, 1962. Today SL&U 751 sees frequent service at the Western Railway Museum.

Special thanks to Rick Borgwardt for corrections and additions to this story.