SACRAMENTO NORTHERN MEMORIES

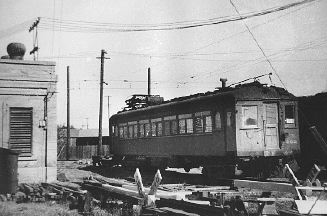

It was the spring of 1952. Mid-week, after school, I spotted the Sacramento Northern MW 302 (ex-steel passenger motor 1020) on the house track at the Concord depot. I wondered what was happening. It was common for the MW 302 to be stored on the substation spur, but not the house track. Something had to be up!

On Saturday morning I got myself down to the depot early and the trolley pole was up. The dynamotor compressors were thumping away. I thought that maybe some kid had put the trolley pole up and run off. As I got closer a young man appeared in the vestibule door. He wanted to know if I was a Boy Scout. He told me that the Boy Scouts from the Montclair District in Oakland were going to take a trip in the car from Concord to Oakland. The SN went through the Montclair District and this trip was being made in conjunction with railroad month in the Scouting program. SN-WP was doing this as part of their public relations events. The SN was always good to the Scouts, providing them a free boxcar for their annual paper drive in Concord.

Normally this trip would have been made from Oakland to Concord. On this day the freight train had to depart from 40th & Shafter in Oakland before daylight in order to make the connection with the SN Detour train at Port Chicago. For that reason the trip was being run in reverse from Concord to Oakland.

The young fellow on the MW 302 turned out to be an SN car man who was sent out from Oakland to sweep out the car and turn on the heaters to warm it up. The man and I got into a discussion about the dynamotor-compressors, what all the jumper plugs were for and the operation of the air brakes.

In a little while, about ten automobiles showed up and about 50 kids piled out and scattered all over the place. By their uniforms, most were Boy Scouts. They were accompanied by their younger brothers and sisters, all taking a ride out in the country, as Concord was then. In a few minutes the SN electrical engineer (whose name I never learned) walked over from his camp car on the ground near the hay barn. He offered to give the Scouts a tour of the substation. The engineer cautioned everyone not to touch anything due to the high voltage. I was fourteen years old, about the same age as the Scouts, so I decided to tag along.

The electrical engineer went on to explain that the substation could not power the train by itself, but needed help from the other substations as they were connected by a continuous feeder system. The motor generator would start automatically when the line voltage dropped to 1400 volts. The electrical engineer could tell by the meters that the Lafayette substation was on and that a train was underway from Port Chicago to Concord. Rather than wait for the motor generator to start automatically, he decided to start it manually. What a lot of commotion that was! It started with the sound of gushing air and a buzz like the sound of a high voltage short circuit. Then it settled down to a loud whine as it gained speed. Upon reaching top speed, it would hunt above and below synchronization for a few seconds. Then came a great clatter of air switches and a big blue arc as the DC generator cut in on the line. After a few seconds of hunting in and out of sync, it all settled down to a loud whine as it turned out the DC current to boost the power for the approaching train.

I was a 4-H Club member and one of my projects was electricity. In fact, I was the 4-H County Award winner in 1952 for my electricity project. I was really taking all of the engineer's explanations in, and he realized that. To me it meant something. The Boy Scouts were saying, "Say, is all this thing does is make noise?"

Upon our exit from the substation a WP/SN official had arrived (possibly Arthur Lloyd) who had been railfanning at Port Chicago. He immediately wanted all of the kids rounded up out of the substation and onto MW 302. He knew that the westbound freight was only a few minutes away. The official was disturbed with me because I made no move to board MW 302. He didn't know that I wasn't a Scout.

As the Scouts boarded, the approaching freight train could be heard at a distant grade crossing. The train consisted of motor 660 on the point with engineer Les Paul, seven or eight boxcars, a caboose, and motor 661 on the rear as a pusher with Mr. Hutchins as engineer. The 661 and the caboose were cut off and MW 302 and its load of Scouts were pulled off the house track. The train was reassembled with 661 on the rear, the caboose, MW302, the freight cars stretching out to motor 660 in front.

Les Paul was always yelling at me. He would say, "Hey, Red, you a railfan?" I would say, "Naw, naw." Then he would say, "Hey, Red, bleed the air off those cars. Hey, Red, get out here and help pass the signals." And I did without saying a word. After the train was assembled, Les Paul hollered, "Hey, Red, get on back there." That was something I would dearly love to have done: ride MW 302 to Oakland. But what went through my mind was, "How would I return home to Concord. Did the Greyhound buses run on Saturday? Could I catch one at 40th and Broadway?" My parents didn't know where I was, and I had no money. I thought that the Scouts had paid their way, or I would have gotten on for sure. It wasn't until I began this story in 1993 that I learned this was a public relations event and free to the Scouts. There were only two such Boy Scout trips made, as the insurance for MW 302 was discovered to cover employees only.

Walter Butterfield was the conductor and he was grumbling as he boarded MW 302. He didn't know what he was going to tell the Scouts about railroading. As I watched the train pulled across the Clayton Road grade crossing. The carman gave the train a standing brake test and turned the retainers up. It was the first time I had seen that done. The reason the brake test and retainers were up here in Concord was that the carman was needed at Port Chicago to start up a diesel for a crew that would go on duty there that afternoon. Normally the brake test would have been done at Moraga and the retainers put up at Havens, but today the train would remain intact and there would be no switching enroute. There would only two stops: to flag the SP San Ramon Branch crossing at Las Juntas, and the summit brake test at Havens where the brake test card would also be put in the box. With the test finished, lead motor sounded two long blasts on the air horn and the rear motor responded with two long blasts in acknowledgement. Then the train left town with its load of Boy Scouts.

The carman hollered at me, "Hey, Red, want to ride over to Port Chicago with me? Have to start up a diesel loco for a crew that will go on duty this afternoon." I said sure. His truck was a 1952 GMC one-ton pickup assigned to the SN car inspectors working out of 40th and Shafter in Oakland.

As we drove out Port Chicago Highway, the car inspector said he needed to stop in Clyde for a few minutes to replace a journal brass on a flatcar with a hot box. This flatcar was loaded with containers going from Oakland Army Base to Concord Naval Weapons Station for storage. Upon arrival at Clyde, the first step to replace the journal brass was to jack up the journal box with a small hydraulic jack. The jack had a small leak and wouldn't stay up as long as the carman would have liked. With the journal box jacked up, the journal brass rolled around the journal into the bottom of the box--something it definitely wasn't supposed to do. Because everything was still quite hot, the carman secured some cotton waste from the truck to wrap his hand to prevent burns. To retrieve the brass, some careful maneuvering was required to work the leaky jack with one hand while fishing for the journal brass with the other. After many minutes of struggle, the brass was retrieved and a new one was installed.

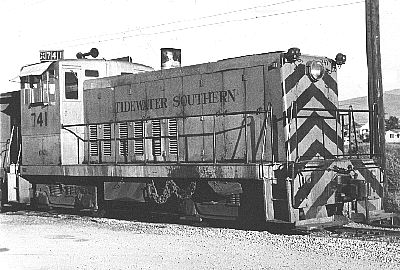

Then it was off to Port Chicago to start the diesel. I asked him which diesel engine it was. He said he didn't know except that "it's one of ours", which meant to me that it could be a Sacramento Northern engine, or Tidewater Southern, or even one from the parent road, the Western Pacific. The SN and the TS were wholly-owned subsidiaries of the WP. The TS was a former interurban electric line like the SN, which ran from Stockton to Modesto and Turlock, with a branch to Manteca.

As we pulled up to the Santa Fe depot, it was apparent the engine was Tidewater Southern 741, a General Electric 70-ton diesel. The carman was disturbed, as this was an engine notoriously hard to start. What surprised me was its fresh California Zephyr paint job, resplendent in orange, silver and black. The last time I had seen this engine, it was in solid black with silver letters and numbers. Another surprise was the engine was live, that is, idling all by itself. What a relief for the carman.

The carman went ahead and inspected the engine, checking headlights, bell, oil, water, fuel, and air brakes. Next he signed his name, date and time on the inspection card from its holder. Then he went over the engine operation with me, showing me the reverser, points on the throttle, and both the independent and train line brakes. Then came my big moment: I sat in the engineer's seat, put the engine into reverse, and opened the throttle one point. The engine started to move. Then I closed the throttle and set the brakes. The carman scolded me some, as I almost "big holed" it, or put the brakes into emergency application. He said that would have hurt my ears.

Tidewater Southern 741 was my favorite diesel, as it made great sounds. It was equipped with the best "goose honker" air horn that the WP also used on its mainline diesels. Its prime mover was an inline six-cylinder Cooper-Bessemer turbo super-charged diesel which also sounded great. As a solid black engine, the 660-horsepower locomotive had made many trips through Concord in 1950.

The carman dropped me off in downtown Concord on his way back to Oakland. I walked back to the SN depot to get my bike and rode home to tell my family all my adventures that morning. After this day's experience, I didn't worry about the Scouts and their ride to Oakland. I got to run my favorite engine with all the great sounds. Everyone should have a day like that.

This story originally appeared in a slightly different form in the Concord Historical Society Newsletter for November 1996 and July 1997. Special thanks to the Concord Historical Society for allowing it to be republished here.