BOX MOTORS, THE SN'S FORGOTTEN STEPCHILDREN

The Sacramento Northern and its predecessors owned three true box motors during the line's electric days. Although these cars were among the least useful equipment the line owned, the railroad still found various ways to squeeze maximum value from them.

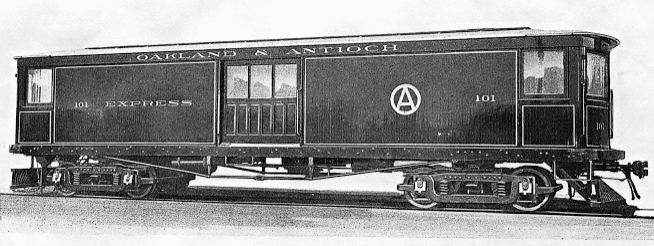

The Oakland & Antioch bought the first box motor from American Car Company (a Brill subsidiary) in 1912 even before the line was completed. O&A 101 was a composite wood and steel car with a distinctive flat roof and exposed steel side sills. The car was featured in early Brill catalogs where it was shown on Brill 27-MCB-3 trucks. Throughout its service life, the car rolled on the same Baldwin 79-30B Master Car Builders trucks used under OA&E's passenger cars. Like the passenger cars, the express motor was ordered just as a body, and was motorized upon arrival. According to surviving records, O&A 101 was driven by four rare Westinghouse 321 motors rated for 90 horsepower each. O&A 101 could operate on either 600 or 1200 volts DC (later 1500 volts for all box motors, with a corresponding increase in horsepower). The car carried two trolley poles. A Brown Roller Pantograph was mounted above the centered baggage doors, and the car was also equipped with roof-mounted signal trippers, making 101 capable of running under Key System wire. The car was 45', 9' 4" wide, with a 12' height at the roof, and weighed 78,000 pounds in working order.

A second box motor was also delivered in 1912 as O&A 102, but was built by Holman Car Company of San Francisco. It was similar to 101, except for having its side sills covered by the body sheathing and a clerestory roof. The clerestory roof was replaced by a less decorative arched roof in 1914. O&A 102 also rode on Baldwin 79-30B trucks. The car was originally equipped with GE-205 motors, each rated for 75 horsepower. In 1916 these were swapped out for 120 horsepower Westinghouse 322E motors from combine 1051. Fitted out with the same Brown Roller Pantograph and roof trippers as 101, 102 was also up to Key System standards. This car also weighed 78,000 pounds, and was 45' long, 9' 4" wide, but had a height of 12' 8" (after rebuilding). Both box motors were equipped for multiple-unit operation, and were frequently run together.

Like many other interurban lines of the time, the O&A management anticipated developing a lucrative express and package freight business. The line even owned a dedicated express trailer, number 0107. In the meantime, the two box motors were put to work hauling construction trains and general freight. On weekends, they were sometimes paired on picnic excursion trains. These excursions were sometimes sponsored by subdivision developers who were covering the hills east of Oakland with new suburban neighborhoods. The railroad saw these housing projects as potential source of future passenger revenue, and was happy to cooperate with the builders.

While the subdivisions may have eventually helped the railroad's passenger account, the express business never took off and the box motors were underused. Whatever express and package freight traffic there was could be handled in the baggage sections of the line's combine motors on regular passenger trains. The seldom-used express trailer was eventually downgraded to a maintenance-of-way car.

The new Oakland, Antioch & Eastern management reassigned the two box motors to general freight duties. For several years they powered the Cannon Ball, a high-speed overnight freight train between Sacramento and Oakland that offered morning delivery of fresh produce to Bay Area markets. Later the two box motors were relegated to switching, branch line work, light freight duty between Moraga and Concord during the fall fruit season, and maintenance-of-way service. During much of World War I, OA&E 101 was rented to the Tidewater Southern.

Although the box motors continued to pull freight trains throughout their careers, they were much less powerful than other OA&E freight motors. Over flat areas they could draw up to 450 tons, but this dropped to as little as 75 tons eastbound on the 4.6 percent ruling grade between Oakland and Havens. By comparison, Baldwin steeple cabs 603 and 604 could pull up to 1000 tons on flat track, and were rated for 150 tons out of Oakland.

Surprisingly, the San Francisco-Sacramento Railroad added a third box motor to the roster in 1924. Why the line built another box motor is an interesting question, when the two they already owned were underutilized. Building a box motor in-house was certainly much cheaper than a new freight motor from GE or Baldwin, and given the line's poor finances, this made considerable sense. Using the electrical equipment from scrapped combine 1051, the former Danville Branch car, the new box motor was built from the ground up in the Oakland shops. SF-S 107 was similar to 102, though slightly larger at 48' 9" long, 10' 1" wide, 12' 8" high, and having exposed steel side sills like 101. She also rode on Baldwin 79-30B trucks, but was powered by four General Electric 205 motors at 75 horsepower each, the same motors originally under O&A 102. Strictly a 1200 volt motor, she was never fitted with third rail shoes for service on former Northern Electric lines. The box motor did have a pantograph platform above the baggage door, but there is no record of a pantograph ever being applied, nor did the car have roof trippers. The lack of these two features meant 107 could not operate under Key System wire. Although 107 weighed 85,000 pounds, the car was rated for the same tonnage as her lighter sisters. Like the two other box motors, 107 had multiple-unit connections, and was said to run especially well with 102, though how often this happened is not known.

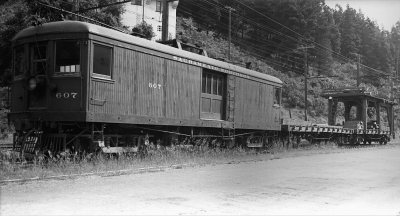

Just before the SF-S's merger into the Sacramento Northern Railway, the three box motors were renumbered as 601, 602 and 607 in December 1928 to avoid conflict with former Northern Electric's Niles passenger cars. Although 601 and 602 were equipped with third rail shoes, there is little photographic evidence that the motors saw much use on former Northern Electric Railway lines north of Sacramento, although they were sometimes repaired at Chico and were occasionally photographed there. SN 601 is known to have worked the Vacaville branch in the 1930s. Otherwise, she appears to have spent a great deal of time at Moraga, and was sometimes assigned to maintenance trains based there. SN 602 was also frequently photographed at Moraga, and along with 607 did switching at Concord. All three motors were frequent visitors to Sacramento.

SN 607 met a tragic fate in September 1938. The box motor was parked in Concord next to a grain warehouse which caught fire. The motor's roof and one side were badly burned. SN 607 was towed to Chico and was set out on the deadline. Although her motors and controls were undamaged, 607's electrical equipment was never applied to a trailer car. By then passenger service was winding down, and there were already plenty of surplus passenger motors. The hulk was scrapped along with the passenger fleet in December 1941.

With traffic booming during World War II, the WP management shuffled several pieces of electric equipment around among their various interurban subsidiaries. In late 1943, Tidewater Southern 106 was leased to the SN. The powerful GE steeple cab was very useful to the SN, and saw both heavy switching and mainline freight service. In exchange, the TS received SN 601 and 602. They were not as powerful, but more than adequate for the limited amount of electrified track the TS still operated at Modesto. It was during their Modesto sojourn that both motors finally lost their Brown Roller pantographs. They were likely removed and scrapped at the CCT shops in Stockton, where the cars were serviced. Curiously, 601, at least, still had roof trippers when the car returned to the SN.

As traffic returned to normal levels with the end of the war, the two box motors made their way back to the SN. By August 1945, SN 601 was back in Oakland, and is known to have worked the Woodland branch in late 1946. SN 602 was photographed at Modesto as late as February 1946, but worked at Concord in the fall of that year.

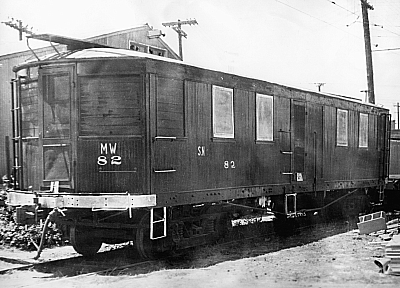

With wholesale dieselization of the SN's North End after 1947, there were more than enough Baldwin and GE steeple cab motors available for the still-electrified Yuba City, Oroville and Chico sections, and the lines south of Sacramento. The two box motors were now surplus, but there was still some use to be squeezed from them. In January 1948, the Mulberry shops converted SN 601 to a lowly bunk car numbered MW 82. In April 1948, SN 602 emerged from the shops as bunk car MW 83. In this humble status, the two cars served in the SN's outfit trains for another 15 years.

In 1963, the SN finally set the two cars aside as surplus. Both were offered to the Bay Area Electric Railway Association, and MW 83 was moved from a siding at Dozier to their museum at nearby Rio Vista Junction. The museum members returned to Dozier the next weekend to collect MW 82, but found that the car had mistakenly been burned for scrap during the week.

The SN lines also owned two passenger combines which achieved near-box motor status, although they were always considered passenger power. Previously mentioned OA&E/SF-S 1051 was hideous flat-roofed car, originally a Central Pacific combine built in 1873. Nicknamed "The Alligator", this leaky monster worked the Danville branch between 1913 and 1924. It frequently pulled freight cars on the branch. The second car was NE/SN 125, built in the Mulberry shops in 1909, one of the stately "Niles copies" which complimented the line's original Niles-built motors. The baggage section of this car was eventually expanded to fill most of the car, leaving just 16 seats and three side windows. In 1940 SN 125 was marked for rush shipments of fresh fruit to Sacramento to Oakland during the harvest season and was nicknamed "The Berry Car". Unfortunately, the SN was underbid by truckers and the car never saw use in this service.

Some of the information in this story came from Ira Swett's CARS OF SACRAMENTO NORTHERN, and SACRAMENTO NORTHERN (1949 edition). Full citations may be found in our bibliography section. Information about 601 and 602 on the TS came from dated photographs, and from Joseph A. Strapac's article "Tidewater Southern Railway, the Story of a One-time Interurban", PACIFIC NEWS, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Burlingame, Calif.: Chatham Publishing Co., January 1974). Additional facts and corrections are courtesy of Peter Hinckley and Robert A. Campbell, Sr.