SACRAMENTO NORTHERN'S SOUTH END FLAGSTOP STATIONS

The Oakland, Antioch & Eastern served few large communities between its two end points, Sacramento and Oakland. Concord, Walnut Creek, Moraga, and Pittsburg were large enough to justify manned stations, in part due to a large volume of freight business. The many small communities in the Oakland Hills served by the railroad, and the occasional ranch in the Sacramento Delta, were merely flag stops. Lacking an agent at these out-of-the-way places, passengers bought their tickets directly the train conductors. For this level of business, it was a most satisfactory arrangement, and lasted through the San Francisco-Sacramento and Sacramento Northern years without any major changes.

When the railroad first opened in 1913, the OA&E provided shelters at many of these flag stops. They were small wooden buildings which gave passengers minimal protection from the elements. The original design, plan A-11, was 12 feet wide by 8 feet deep with unglazed arched windows on each end and an open arched doorway opening facing the tracks. Most appear to have also had an arched window opening in their rear walls. The walls were clad with novelty siding. The shelters were capped by hip roofs covered with asphalt shingles. Large boards with artfully dressed corners and bearing the stations' names were mounted on the roofs at each end facing arriving trains. These shelters sometimes sat on wooden platforms, especially when the ground sloped away from the tracks. At other locations the shelters were placed directly on the ground.

The shelters' original color scheme is not known, but the walls were a light color, with a darker trim. The large stations at Walnut Creek and Concord give us clues to the colors used in later years. Catenary Video Productions' video SACRAMENTO NORTHERN IN 1940 includes a fine view of the Walnut Creek depot, which clearly shows pale yellow siding with medium gray trim. The Concord depot, on the other hand, was yellow with oxide red trim. Views of the shelters themselves from this video are rather washed out. It appears that by 1940 both the walls and trim were pale yellow, or perhaps a light buff, though the trim cannot be seen clearly in any of the scenes. Both oxide red and dark green shingles were used on the roofs.

Standard A-11 design shelters were known to have been located at Canyon, Bancroft, Thornhill, Burton, West Lafayette, Lafayette, Saranap, Pleasant Hill, Molena, Walden, Adeline, Meinert, Ohmer, Nichol's, Dutton, and Garfield. A similar design was found at Mallard, though this one had a rectangular door opening and windows. There were probably several more built to the original OA&E design, but railfan photographers rarely pointed their cameras at buildings, and information about the shelters is largely limited to photos where they appear in the background of action shots.

A slightly larger version of the standard design was used at some busier locations. These shelters appear to have been about 15 feet wide, and might have been about 10 feet deep. One of these originally stood at Meinert, the junction with the Walwood Branch. The Meinert shelter was sited between mainline and the branch track, with its short window ends facing the diverging rails. From a photo in Swett's Sacramento Northern, it appears that the building had an arched portal on both of its long sides. This made the structure little more than a roof supported by corner columns, and it must have been very windy and wet during storms. This shelter was later replaced by the smaller standard design.

Several shelters departed completely from the original OA&E design. Some may have been replacements for earlier buildings that were damaged or simply outgrown, while others were makeshift affairs built at minimum cost. Their different styles suggest they were the work of later managers, likely during the SF-S years.

Saranap, the junction for the Danville Branch, had a non-standard shelter, a replacement for a smaller building of the A-11 design. Saranap's shelter was nearly square, probably 8 or 10 feet on each side, and its end windows were rectangular. Although the entrance was the familiar arched portal, the building was blocky, out of proportion, and had none of the charm of the smaller shelters.

In 1924, the A-11 shelter at Pinehurst was replaced a larger structure measuring 10 by 12 feet. It had a hip roof, but the eaves extended much farther beyond the walls than those of the standard shelters. The window and door openings were rectangular, with small window openings on either side of the door. The building was supported by pilings on a steep slope, and was surrounded by a very substantial platform.

Sequoia was another unique station. According to some sources, local residents were unhappy with the original shelter provided by the OA&E, and paid for a more stylish replacement. The second shelter began as a small shingled building, perhaps 10 feet square, with a peaked roof. The roof was later extended on both ends, and was supported by wooden columns without walls, thus adding two open sections. A porch with a peaked roof was added at a right angle to the front of the center section extending toward the tracks.

Several other shelters were also unique, though they could hardly be called designs. Raliez, between Lafayette and Walnut Creek, was provided with a shelter of rough upright planks and a peaked roof that was strongly reminiscent of an outhouse. By the end of passenger service, this little shelter was kept standing by diagonal braces crudely nailed to the ends. Kilgore was provided with a simple shelter similar to the one at Raliez. The rude shelter at Las Juntas, a junction with the Southern Pacific's San Ramon Valley Branch, was also of upright planks with a dreary flat roof, and resembled a chicken coop. West Pittsburg's shelter was also crude, a peak-roofed little building clad with board-and-batten siding and pierced by several rectangular windows, glazed for a change, perhaps because of strong winds off the Delta. Montezuma's shelter (still standing) was a peak-roof structure covered with corrugated sheet iron, which must have been like an oven during the summer. The spartan nature of these buildings suggests that traffic from them was not particularly important, so only a minimum was spent on comfort for the occasional passenger.

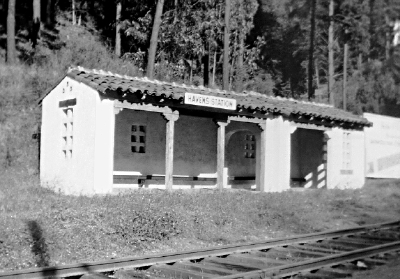

The lovely station at Havens was an entirely different case. Havens, a failed suburban development of Frank C. Havens and Francis M. Smith's Realty Syndicate, was provided with an attractive masonry and stucco building in the mission style. The structure is similar to stations on the Key System (also a Havens-Smith property), and was actually built by the Realty Syndicate. It was probably in the range of 15 by 40 feet. The left side was open to the tracks with the roof supported by two square columns. The right end was semi-enclosed. The roof was peaked and covered with terra cotta tiles.

The mission style was used again for the line's largest flag stop shelter at St. Mary's College. This station was actually owned by the school, not the Sacramento Northern. This building was about 15 by 70 feet. The open section to the left was similar to Havens, except for having a flat roof with terra cotta trim around the edges. The center was a semi-open section, made to appear as a short tower a bit taller than the two end portions, and featuring a hipped terra cotta roof. "St. Mary College" (curiously, without the "s") was spelled out in classy raised metal letters on the building front. The right end was enclosed, and all known photos show a blank wooden door and filled window facing the tracks. The room was probably used for storage, though it may have been intended as a small freight room or ticket office. St. Mary's was the last flag stop built on the SN's South End.

Many passenger shelters were accompanied by small open-front salt-box sheds for light freight and express. These were built on short legs to make their floor level with the car baggage doors for easy loading. Such platforms are known to have been used at Lafayette, Dutton and Walnut Creek, and it is likely there were others. Meinert and Rio Vista Junction had small freight houses, though they were unmanned throughout much of the line's history.

With the end of South End passenger service in 1940, most of the shelters were destroyed by the SN to lower the railroad's taxes and avoid liability lawsuits. It was a slow process, and the shelters at West Pittsburg and Burton were still standing in the early 1950s. One of the original arched-window shelters, possibly Ohmer, was moved to Concord where it served as a maintenance or storage shed for a few years. The substantial depot at St. Mary's College continued to be used as a shelter for the bus line which replaced the trains, though it was eventually destroyed in 1993.